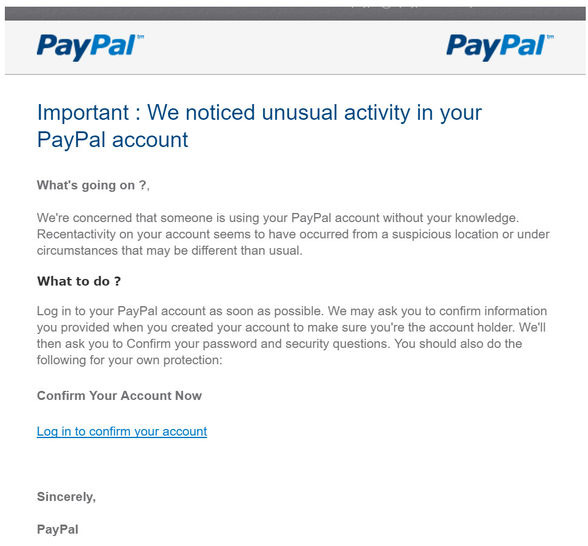

The other day, I received an SMS from Uber containing a two-factor authentication code that I hadn't asked for. Panicked by the prospect that someone was trying to hack an account that stores my credit card details, I embarked on a flurry of password-changing, starting with my Outlook.com account—where I found an email from PayPal informing me that my account had been compromised. Now doubly panicked, I clicked the enclosed link to log in and change my password, and was about to enter the last character of my current password when I glanced at the URL in the toolbar—it didn't say paypal.com.

As a relatively tech-savvy person who writes about internet security, I'd nonetheless been the target of two nearly successful scams in the space of an hour—what gives?

"Cybercrime is growing, and one of the biggest areas is credential-stealing—the theft of someone's login details," says Jon Clay, director of global threat communications, Trend Micro. Login credentials are valuable—and to obtain them, cyber criminals try to infect users' machines with threats such as trojans that can spy on all activity on a computer, keyloggers, which can track inputted characters, or spoof screens that invite unwitting users to voluntarily give up their username and password (known as phishing). Once criminals have these details, they can not only breach the account in question, but potentially set into motion a daisy chain of account breaches that could lead to identity theft.

"In the vast majority of cases, cyber criminals are trying to obtain money," Clay says. Ransomware is a form of malware that entirely bypasses credential-stealing to encrypt a user's device, rendering it and its files inaccessible unless a ransom is paid. And the use of ransomware is skyrocketing. Symantec found that the average ransom demanded in such attacks in 2016 was $1066 per person—266% higher than the year before—while on mobile, ransomware attacks have risen by 250%.

Cyber threats, from ransomware to spy software to phishing attempts on valuable logins, commonly gain access to users' devices when users unknowingly click a malicious link in an email, on a webpage or in an online ad. The increasing availability of personal information online via sites such as LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook means that scammers are getting more precise at social engineering—manipulating people to click on malicious links or give up personal information by using seasonal cues, current events or, more insidiously, facts gleaned from their public profiles.

"Social engineering is all about exploiting users' irrational behavior," says Rahul Telang, professor of information systems and management at Carnegie Mellon University, who's currently working on a project examining consumers' security and privacy behavior. "You may know something is too good to be true—that winning lottery ticket, a get-rich-fast plan, a chance to meet your life partner—but the rewards are so high, you think, why not try?"

The chance of making such a cognitive error rises when scammers use language or make offers designed to appeal to our specific circumstances—or when we aren't on guard.

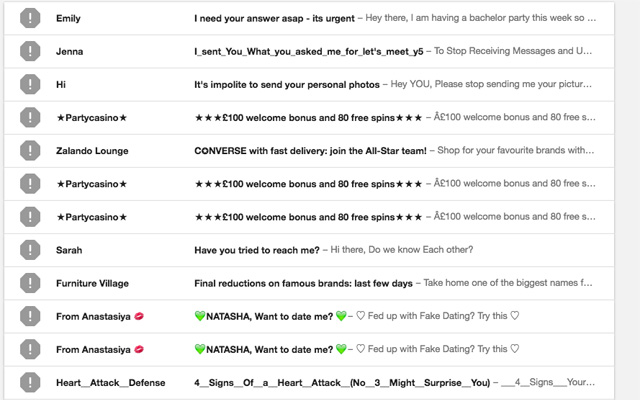

Scammers love email

We all know what spam email looks like—it's the stuff that our email filters normally catch, with subject lines that use our email handle as a first name, notify us of vast lottery winnings or offer various bodily enhancements. But spam filters have gotten so sophisticated that when an email does slip past—as with my PayPal spoof email—we're not necessarily in the right frame of mind to catch it.

"The most common ways cyber criminals can get to you is through your email," Telung says. "When you're checking your emails, even if you're not interested in shopping, if an email says you've got this great deal, you're likely to click."

Scammers' psychological tricks can even include the time of day. "There are many cases where spam is sent at certain times of day when people are less likely to be diligent, such as in the morning," Clay says.

Subject: "Your account has been compromised!"

Spoof emails from financial accounts are on the rise, and this scam targets the rising fear of the consequences of hacked bank (or PayPal) accounts by claiming an account has already been hacked. Users are then exhorted to protect their account by clicking a link to change their password—except they're really taken to a bogus screen that records login details, sending them straight to hackers, who now have access to a previously safe account.

"We are seeing phishing as a big one to steal credentials," Clay says. "In most cases, the link pops up a phishing screen to get details, or downloads a banking trojan that contains a keylogger or runs scripts to transfer funds out of the account."

Subject: "Please check your tax return"

Around tax season, scam emails appearing to be from the IRS tend to make the rounds, says Clay—usually with a request for your personal information or for taxes associated with a large sum of money you've mysteriously come into. These links end up taking users to a phishing screen or a malware download that gives the criminal access to the victim's computer. "Financial scams are often successful because people are concerned about their finances, and if they receive an email about an audit, or their taxes, they tend to take action," Clay says.

Seasonal spam

Holidays can also bring on a wave of seasonal spam, ranging from shopping discounts, which, in a sea of similar promotions from your favorite retailers, can be hard to spot, to greeting cards from email addresses that appear to belong to friends or family.

"Black Friday is a big one. You might see scam emails offering links to a 50% off coupon," Clay says.

Emails from friends

You may have received an email from a friend purporting to be in trouble overseas and in need of cash, recommending you donate to their favorite charity, or, in a particularly virulent phishing scam earlier this year, with a link to a Google Docs document that led to a Google sign-in page and request to authorize "Google Docs" for email—which would give the scammers control of the user's account.

"Criminals are getting smarter [about getting] access to your social network data," Telung says. "It's easier for them to impersonate someone close to you and send an email that you're more likely to trust."

What to do:

- Be very wary of any email that tries to get you to click on a link or open an attachment, especially if it involves some urgency, Clay says, such as a breached account or friend in distress. Stoking panic is one way of pushing users into a state of mind when they may be less vigilant about looking for signs of fraud.

- If you're on a computer, hover the cursor over a link you're being asked to click, and check the bottom left of your browser window—you should see the true URL you'll be directed to.

- Check with your financial institutions for guidelines describing the type of communication you can expect. For example, the IRS doesn't initiate contact to request personal or financial information, while PayPal emails always address the recipient by first and last name—which my spoof email did not.

Bad ads on good sites

Nobody loves online ads, but the last year has seen a spike in the prevalence of "malvertising," malware-ridden ads that redirect browsers to phishing sites or sites that serve more malware.

"A lot of people still click on ads. Criminals are now targeting legitimate websites with malvertisements designed around current news events or the time of year—such as tax time, Christmas, Black Friday—that invite users to click a link that ends up infecting their computer with malware or ransomware," Clay says.

Because of the way online ads are served via third-party automatic platforms, websites' security controls usually can't detect or block malvertisements. Like online ads, which appear to certain users based on their past browsing, malvertisements can be targeted to particular profiles and times of year, making it all the more likely that an unsuspecting user will click on an appealing offer, especially when the ad appears on a trusted site, such as The New York Times, Newsweek and MSN—all of which were hit by a major malvertisment attack last year.

In many cases, users don't need to click on the ads to be infected: Malicious script can run as soon as the ads loads—an attack known as a drive-by download.

What to do:

1. Download all security patches for your OS, browser and other programs. Malware works by targeting security holes in browsers and plugins, most notably Flash or Java—both of which are notoriously full of vulnerabilities. If your systems are up to date, malware has a lesser chance of slipping in undetected.

2. Enable "click-to-play" for plugins such as Flash and Java. This stops plugins from automatically running page elements, including ads, until you click them. You can find this in your browser's Settings menu, under Plugins.

3. Uninstall plugins you don't use. The more plugins, the more potential vulnerabilities there are for a drive-by download to target. Websites are increasingly eschewing Java, for example, and Microsoft's Silverlight plugin, once essential for Netflix and some radio stations' "listen online" options, is also far less prevalent.

Finally, "avoid clicking on things you weren't looking for," advises Telung.

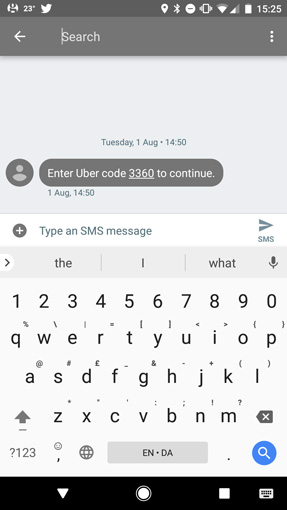

Unsolicited two-factor authentication texts

Many accounts, from banks to Gmail, use two-factor authentication to protect users' data by requesting a code, often sent by SMS, in addition to a password. However, researchers recently demonstrated that it's possible for scammers to spoof these texts.

In the scam, the criminals try to log into the account—or change the password—which would trigger the SMS code to be sent, as occurred with my Uber account. After that, a second—spoofed—SMS requests that the user reply with the code to confirm that the account is theirs—thus delivering the authentication code into the hands of the hackers.

What to do:

1. If you haven't tried to log into your account or change your password, ignore such texts.

2. Never reply to these texts with the authentication code or any other login details.

3. Change your password.

4. Where the accounts support it, change the code delivery method from SMS to an authenticator app, such as the ones used by Gmail and Outlook.

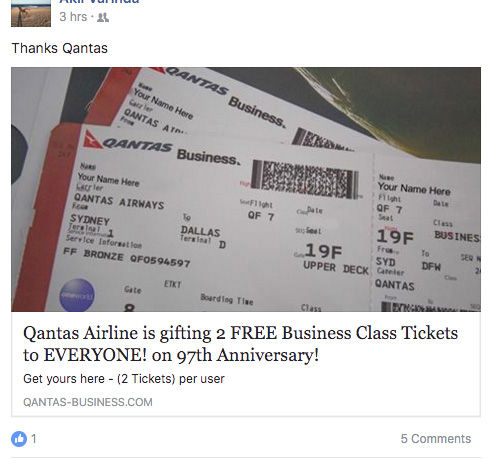

The 80% off sale

Whether it's free business-class flights to Australia or a clearance sale on totally authentic designer sunglasses, scams circulated via Facebook were the most common online attack method in 2016, according to Cisco's annual security report.

One prevalent scam involves spoof pages for trusted brands advertising unbelievable sales, which are shared by unsuspecting Facebook users. These ads then appear in their friends' feeds—and because it appears as a recommendation by someone they know, they're all the more likely to click through. The links may lead to phishing sites that make a play for credit card details, or to legitimate-looking online shops where victims end up purchasing counterfeit goods.

What to do:

1. Look up the website or company name—often, if it's a scam, others will have fallen prey and posted about it on site-review websites such as Trustpilot or Reviewcentre.

2. Look up the URL registration at Whois.net, which will tell you how long the domain has been active, among other details that should give you an idea of whether the site is legitimate.

3. If the site appears trustworthy, make sure the transaction is done over a secure (https) connection.

4. Use a credit card, not a debit card—credit transactions can be reversed by banks in case of fraud.

Securing the digital gates

Awareness about cyber fraud can go a long way to avoiding malicious links and sites, but as scams become more sophisticated, internet users will need to be increasingly dependent on software providers that can detect an ever-evolving array of cyber threats.

"Criminals are really starting to target legitimate websites with malvertising, redirects to bad sites, and malicious scripts that download malware as soon as the site loads," Clay says. Where human error is still the "in" for most cybercrime, the rise of threats such as malvertising and drive-by downloads that can infect a user's computer with barely any interaction means that strong security software is more crucial than ever.

"Cyber security is a war between scammers trying to figure out how to get into your machine and the security companies trying to stop them—and the user is just in the middle," Telung says. "At some level, the game can be so sophisticated, even well-informed people may not be able to avoid being scammed. Users just have to hope they have the tools to prevent attacks."

Those tools include a comprehensive security program with advanced features such as firewall, phishing detection and website scanning to flag potentially dangerous destinations. As Clay notes, cyber security is no longer just about blocking viruses.

[Image credits: Anxious woman with laptop via BigStockPhoto, screen shots via Natasha Stokes/Techlicious]