From viral hoaxes about US presidents to doctored images of natural disasters, there’s no shortage of misinformation online. The term ‘fake news’ has become a common call online, used to discredit various articles ranging from inaccurate content to opinions one doesn’t agree with, to satire whose point has been missed. Many people also equate fake news with shoddy journalism or sloppy writing.

But that dilutes the problem, says Peter Adams, senior vice president for educational programs at The News Literacy Project, a nonprofit organization set up to teach students how to separate facts from falsities in online media.

“I use the term ‘fake news’ to refer to misinformation or disinformation disguised as journalism or news,” he says. That definition excludes articles that are written as rumors, as well as hoaxes, memes and doctored images that are created in an attempt to gain attention or virality.

“Calling a piece of misinformation ‘fake news’ when it is not presented as news confuses people and makes it harder to solve the problem,” he says. That tweet about a submerged shark in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, for example, wouldn’t count as fake news in Adams’ book because it was submitted as a user-generated cell phone image (albeit one that has been circulating online for years as part of one hoax or another); similarly, claims made by 4chan forum users about the Las Vegas shooting were intended to go viral, but not designed to appear from a news organization.

“The purpose of most ‘fake news’ is pretty simple: to make money from ad revenue,” Adams says. In Veres, Macedonia, where scores of fake news stories about the 2016 US election originated, the teenagers writing them claimed to make thousands of euros a day.

“Fake news was spread more virulently and had more of an effect during the 2016 presidential campaign, before the American public really became aware of this particular type of misinformation,” says Adams. In the final three months of election season, Buzzfeed News analysis found that fake news stories generated more engagement than major news organizations’ top headlines.

Why we spread fake news

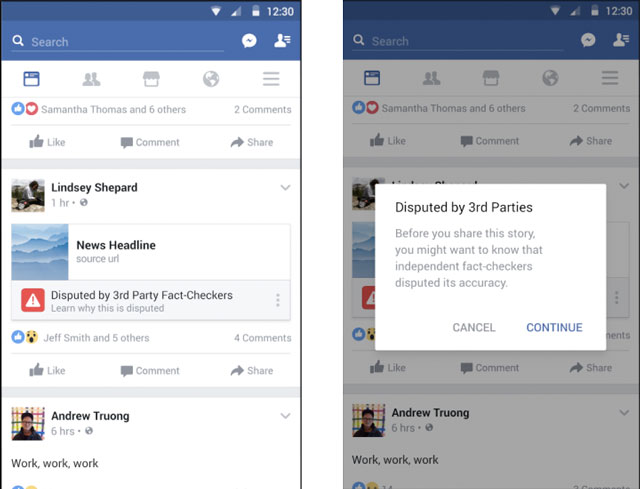

Part of the insidious nature of the fake news problem is how easy it is to create legitimate-looking articles and publish them in the same channels as trustworthy news. Over 40% of Americans now get their news online, with more people than ever getting their news on social media. Personalized smartphone feeds are increasingly replacing the curated editorial viewpoint, and fake articles can easily slip in among posts from friends and articles from trusted media, making it all the more difficult to sort the signal from the noise.

Professor S. Shyam Sundar is a Penn State researcher hoping to solve this aspect, by building an algorithm that can detect and filter fake news articles. “In the online world, there is no clear separation between reliable or unreliable news sources. Our goal is to conceptualize what fake news is, and mark all the news that belong in this category,” he says.

One reason people don’t spot fake news (and go on to share it) is the confirmation bias. “If you come across something that confirms your previously held beliefs, you’re more likely to believe it yourself,” Sundar says. “Confirmation bias is often cited as why people seek out information that aligns with their worldview, and believe certain untruths over others.”

The algorithmic personalization of news feeds on social media and in news apps based on past clicks further amplifies the effect of the confirmation bias, creating the “filter bubble” where users only see news they like or agree with. As well, people tend to disbelieve things that don’t align with their beliefs, further reinforcing their current opinions at the expense of truths that may conflict.

Fake news also gains its traction on social media, where posts are shared by friends, because users have their guard down, Sundar notes. “Over the last 20 or so years, we have found that people have become less vigilant about their sources of information. There has been a decline in the appreciation of traditional journalistic sources and the fact-checking that these outlets perform on their articles,” he says. “A major reason for the fake news explosion is that people are not paying attention to where articles come from.”

Even for the more vigilant, it’s not always easy to immediately tell whether an article comes from a reputable source. “Many people consume news via aggregating apps or homepages, which means that articles can go through multiple sources before landing in front of a reader, making it very difficult for people to parse original sources,” Sundar says.

How fake news hooks you

The more people click on a fake news article, the more money its creator makes—hence the tendency for fake news articles, including doctored images or videos, to follow certain click-friendly formulas. Along with containing false information:

Fake news causes an emotional reaction

Because high rates of engagement such as shares and social media likes help fake news spread, one hallmark of a fake news article is that it elicits a strong emotional response. “You can see the pattern of inventing something that will get a big emotional reaction—usually about something that is already in the news, such as the NFL player protests—long enough to override people’s rational minds and get them to share,” says Adams.

Fake news spikes around volatile events

“When the outcome of a major event is uncertain, that’s always news,” Sundar says. Like the 2016 election period, the uncertainty surrounding the Charlottesville riots caused a spike in misinformation. Established media outlets already feed the 24-hour news cycle with varying angles on unfolding events; fake news creators who know people will search out information on these events are more than happy to oblige with search-friendly articles in order to receive those money-making clicks.

Fake news resembles credible news

Fake news sites abound, with copied logos and layouts of legitimate media sites at URLs that sound almost correct. Some ape existing media while others invent real-sounding newspapers, complete with mastheads. “These tend to be very biased towards one side or another, for example, in politics,” Sundar. “That gets people to pick up the headlines whose viewpoint they agree with, and share them.”

Fake news headlines attract attention

Like a lot of content online, fake news articles lead with headlines designed to grab clicks. Some sensational fake news headlines in the past year have claimed that “Rage Against the Machine to Reunite and Release anti-Trump Album” and “425-pound Teacher Suspended for Sitting on Student”.

Fake news articles have unnamed sources, or none at all

While this characteristic also isn’t unique to fake news, fake news articles that make sensational claims often quote an unnamed “spokesperson” or “sources familiar with the matter”. “Fake news creators often don’t name experts or credible people, because they know these claims can be quickly debunked before the article gets enough clicks,” Sundar says.

The role of mainstream media

Some mainstream media have fallen prey to lapses in fact-checking - and confidence from the public. A Gallup poll found that the majority of Americans don’t trust the mainstream media, with confidence hitting an all-time low last year, just before the contentious election season - which could have left many people open to alternative news sources, some of which may peddle fake articles.

“It may be that the media has been less focused on investigative content in favor of lifestyle journalism that focuses on entertainment, sport or news people can use,” Sundar says. “People need to see more that established empires are indeed questioned with force and vigor, rather than seeing the media as mouthpieces for companies.”

Some mainstream media also operate with a clear bias, also inciting calls of ‘fake news’ from consumers. However, “that’s a different can of worms,” Sundar says. “Media outlets might pursue some stories with more vigor, but if stories put out are false, they lose credibility. If you’re concerned a particular news org is biased with a certain opinion, you’re welcome to switch to another that’s less biased.”

1. Watch your reaction.

“If you are having a strong emotional reaction, stop and think carefully. Is there a chance that this information is designed to make you react? Is it trying to use you as a “spreader” to increase its virality and revenue?” Adams says.

2. Consider the source of the information.

Check the URL - if the domain is something like “.com.co”, that should tip you off. Check the About page to find out whether you’re reading the fact-checked output of a reputable organization, or the musings of an individual. Go through the other stories you find on their website to determine whether the source is trustworthy.

3. Evaluate the piece of information.

“Ask yourself, what evidence and sources does it cite?” Adams says. Search for these sources and data online. Note the tone of the article - does it attempt to present both sides of an issue? Are other media reporting the same thing? If a sensational story is only covered on a site you’ve never heard of, that’s a red flag.

Fact-checking sites such as the non-partisan, politically focused FactCheck.org and Politifact help sort out the true from the false, while Snopes is a reliable mythbuster of various internet rumors.

As well, consider if the article is asking you to do anything beyond getting your eyeballs on it. “Any story that would have its readers take a decision like clicking share, or making a financial or voting decision should be carefully evaluated,” Sundar says.

4. Check images and videos for authenticity.

Copy and paste an image into Google Image search to see where else the image pops up, Adams says. In the case of the shark floating in the street, that image had been circulating for years. For videos, dig into its properties, or look at other videos posted on the same account.

5. Get a second opinion.

“Take a screenshot and send it to someone you know, or to a journalist or fact-checker through social media, and ask them if they have any advice on whether or not this can be believed,” Adams says.

6. Analyze the stories that got you.

“If you get fooled, reflect on how and why, and then guard against someone taking advantage of you in this same way again,” says Adams.

7. Widen your filter bubble.

The stories you read could be personalized to what news or social algorithms have parsed you like, Sundar says. Seek out alternate viewpoints in media you trust, and find one or two unbiased sources of news such as wire services like Reuters or Associated Press.

[Image credit: Fake News concept via BigStockPhoto]

From CRC on October 30, 2017 :: 2:56 pm

Hi! Love the article, may we share this on our social media platforms?

Reply